The Colonel: A Singular Life

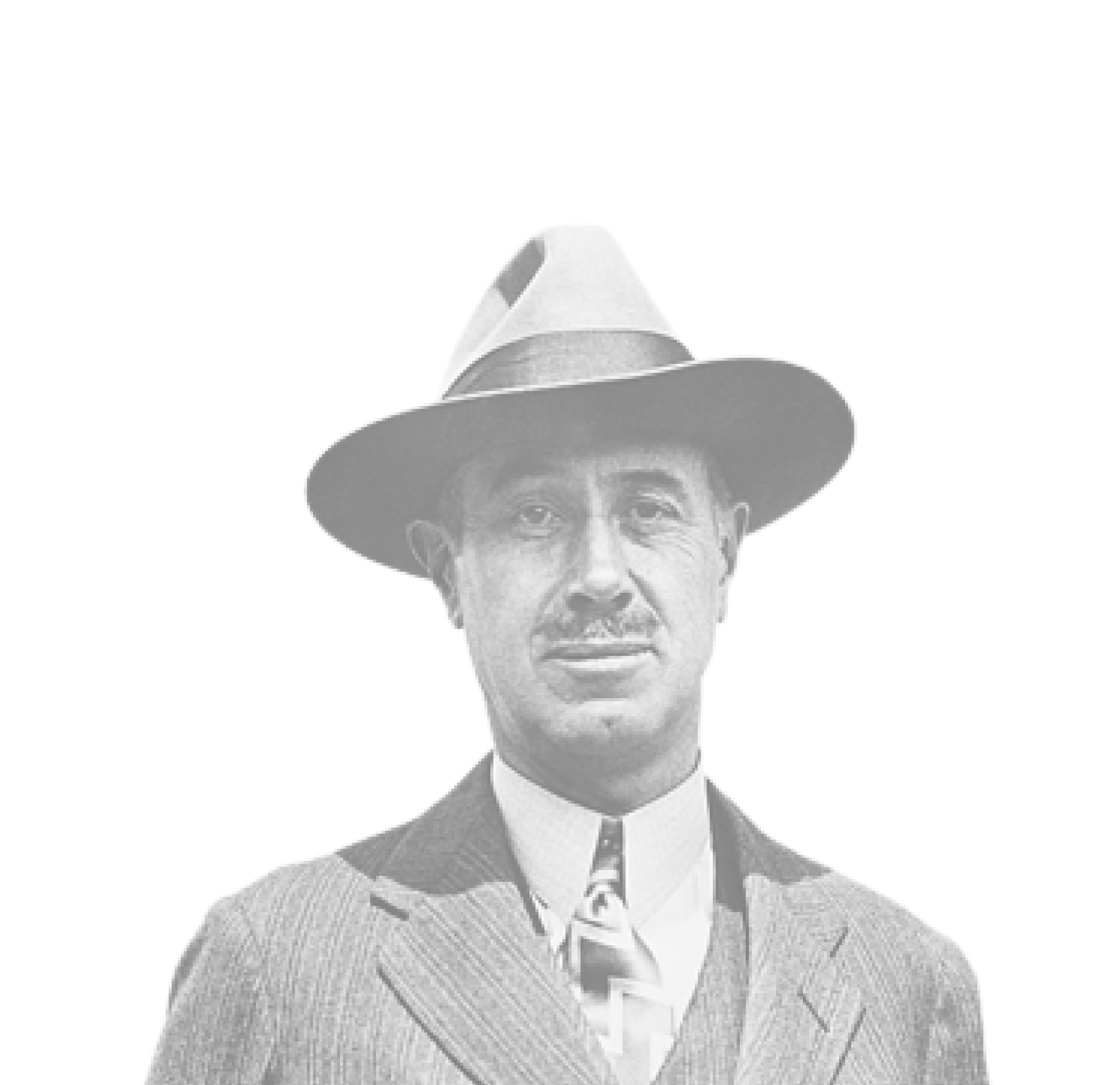

The measure of Robert Rutherford McCormick’s 74 years of life could encompass many lives.

Publisher, editor, media pioneer, and staunch defender of the First Amendment; war hero, explorer, and public servant; civic leader, attorney, and philanthropist. He stood 6-feet, 4-inches and was known as the Colonel, a rank achieved during his valorous military service and a nickname that proved to be an enduring reminder of his imposing presence.

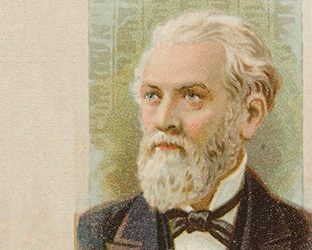

Born July 30, 1880, in Chicago, “Bertie” as he was known in his early years, was the second son of Robert Sanderson McCormick and Katharine McCormick, whose father, Joseph Medill, was publisher of the Chicago Tribune.

At 9 years old, Robert moved with his family to London, where his father served as second secretary in the U.S. Embassy. In what was an early indicator of McCormick’s strong will and spirit of adventure, he taught himself to sail and attempted with a friend to cross the Mediterranean before a ship’s captain spotted them and returned the boys to land.

After returning to the U.S., Robert was sent to the prestigious Massachusetts prep school, Groton, where his headmaster described him as a lackluster student of above-average intelligence. Nevertheless, McCormick showed enough talent to be accepted at Yale, where he thrived and continued his adventurous pursuits, which included hunting with Inuit guides in Hudson Bay.

Back in Chicago in 1903 after graduating from Yale, McCormick started to forge his distinctive path, attending law school at Northwestern University and, at 23 years old, being elected a Chicago alderman on a platform of honest government. One year later, McCormick was elected president of the Chicago Sanitary District. The cynics of Chicago politics poked fun at his noble manner.

They soon understood he was not afraid to get his hands dirty or tangle with opponents. Announcing that merit — not patronage — would determine who gets employment at the district, McCormick fired hundreds of political hacks and replaced them with engineers.

While he might have become a very powerful elected official, McCormick’s life took a turn in 1906, when his older brother, Medill — who had been expected to take over leadership of the Tribune — suffered a nervous breakdown.

The paper’s future fell into further doubt with the death in 1910 of McCormick’s uncle Robert Patterson, editor in chief and president of the Tribune. A year later, McCormick became president of Tribune Company. One of his earliest acts was discouraging shareholders from selling the paper.

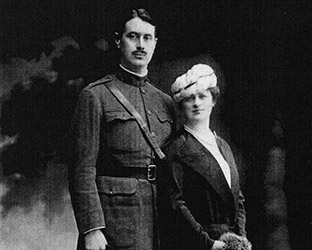

Over a five-year period in his 30s, while leading the Tribune, two fundamental components of McCormick’s personality — a love of adventure and the fierce desire to serve his country — emerged. During that time, he spent his honeymoon touring and writing about war-torn Europe with his bride Amy de Houle Irwin Adams.

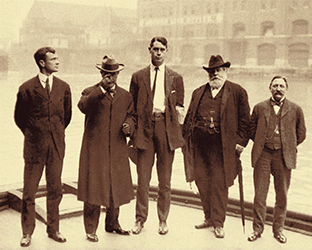

Contrary to what some might expect from a man of his privilege, McCormick enlisted in the Illinois National Guard in 1915 and was dispatched to protect the southern U.S. border against raids from revolutionary Pancho Villa. Two years later, he joined the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I and served in a crucial early U.S. victory in a battle for a French village named Cantigny.

Promoted to colonel in the Illinois Guard in 1918, he received the U.S. Army’s Distinguished Service Medal in 1923 and remained in the military reserves until 1929. As an indication of how indelible his military service was for him, McCormick renamed his 500-acre estate in Wheaton after the French battleground where he served as commander. Cantigny opened as a public park in 1958.

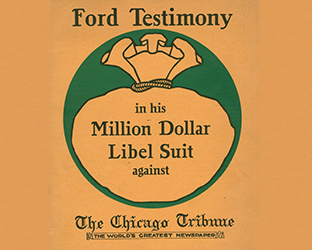

Across the five decades of his leadership at the Tribune, until his death in 1955, McCormick frequently used the prominent platform — his biography called it a “joyously combative conservative broadsheet” — to express his strong beliefs, and as the anchor to what became a media empire that included the New York Daily News, Washington Times-Herald, WGN radio in 1924, and WGN TV in 1948. The call letters stand for “World’s Greatest Newspaper.”

Conservative, isolationist, and aggressive in many of his political beliefs, the Colonel was viewed as a supportive fatherly figure by his employees. His newspaper prospered and Tribune workers were among the highest paid in the industry.

The Colonel also was an ardent defender of Freedom of the Press throughout his life, funding significant cases on the issue, authoring a book about the subject and providing crucial funding to establish and sustain Northwestern University’s acclaimed Medill School of Journalism.

In 1939, his wife Amy died. Five years later, the Colonel married Maryland Mathison Hooper, a close friend of Amy. On April 1, 1955, the Colonel died of natural causes a few months short of his 75th birthday. He was buried at Cantigny, dressed in his World War I uniform.

The Colonel’s last will and testament called for the establishment of the Robert R. McCormick Charitable Trust and stipulated that Cantigny become a public park. Although he outlined a few specific missions for his Charitable Trust — promoting education on freedom of speech was one — he also gave trustees broad discretion. As the will stated, “their [trustees] very long association with me has given them especial knowledge of the ideals and principles which have guided me in the management of the Tribune Company.”

Guided by his final wishes, the Foundation provides significant support for early childhood education, assists communities on the South and West Sides of Chicago, strengthens our democracy through support for journalism and civics education, helps veterans make a seamless transition to civilian life and through Cantigny, provides recreational and cultural amenities as well as military history to the public.

The McCormick Foundation also works to ensure that children and families, especially children, have the opportunity to thrive for generations to come.